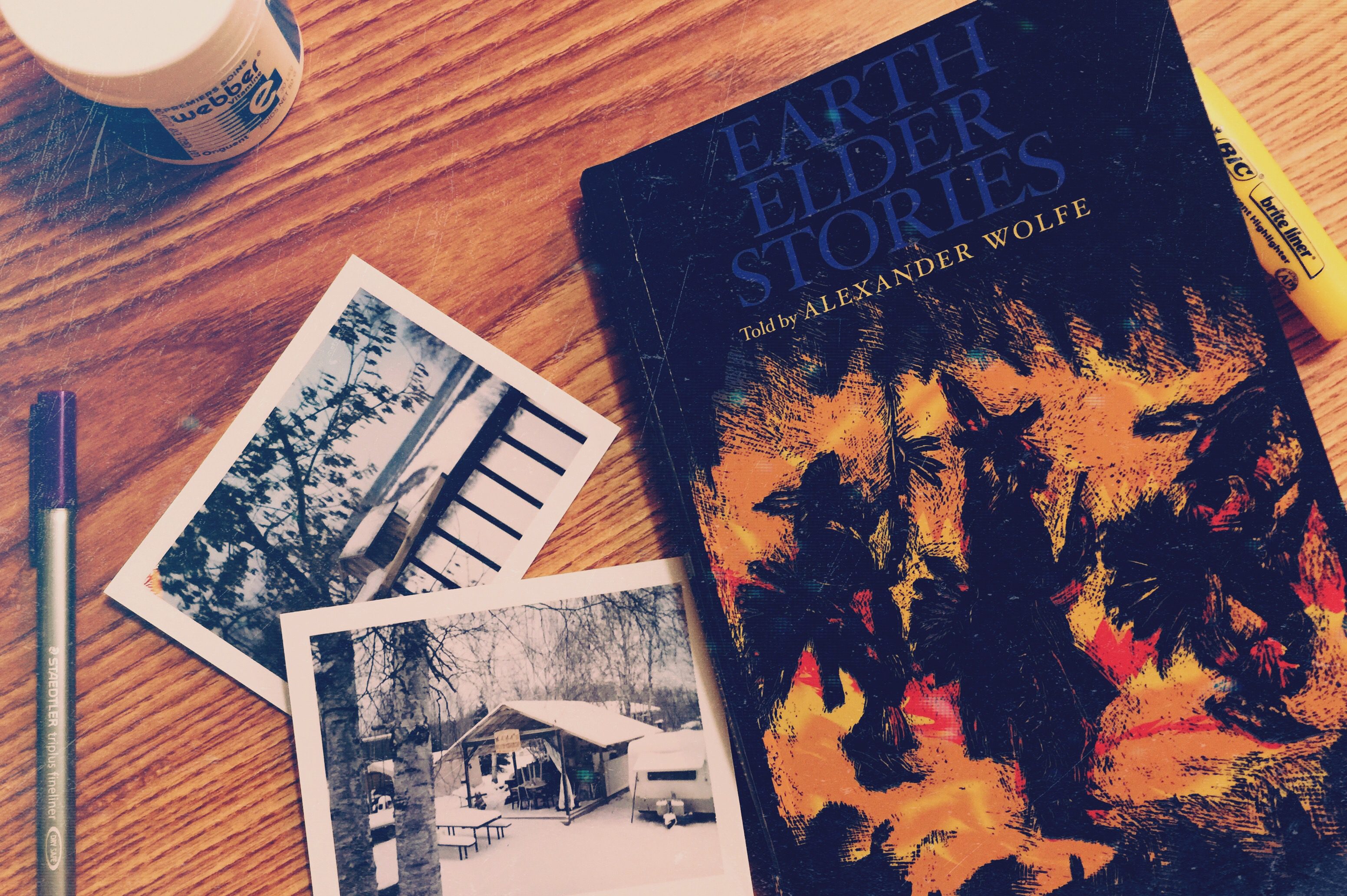

This was first published in 1988 and then again in 2002. The preface was written by Harvey Knight, and an introduction by Alexander Wolfe. This is a collection of stories transcribed by Wolfe, as he remembers them being told to him by his grandfather about his grandfather, Earth Man. In the preface, we see that Wolfe presents “historical accounts in narrative form, interwoven with the significance events, personalities, and notable places, such as the ancestral homeland and sacred pilgrimage sites of his people” (viii). This book is regarded as a “starting point and a guide in the development of written histories of indigenous peoples” (viii). The preface also notes that “the ultimate goal should be to achieve a balance, allowing Indian oral and written traditions to co-exist side by side without one diminishing the importance of the other” (x). Wolfe’s introduction the text tells us that “oral tradition, in which history is embedded, requires the use of memory” (xi) and how he remembers these stories because he was told them over an dover again as a child, and they have become more significant to him as he ages. He tells the reader that “the right to tell the Pinayzitt family stories came to me through my mother. Earth Man had four younger brothers. The third in line was my mother’s father Keshickasheway mingot (Blessed by the Sky)” (xiv). The fact that he notes his familial ties to these stories is important. He argues that “we must turn to a written tradition and use it to support, not destroy, our oral traditions,” (xiv) which is reinstated in the preface by Knight.

There are 11 main stories within this smaller text. Each one states how the story came to Wolfe, and how his Grandfather remembers it. The claiming of his right to tell the story is always introduced. The first story I looked at was The Sound of Dancing (1), and I choose this one because of the disbelief that was stated in the story. The Grandfather said “You must tell all that I tell you to your people – to those who will accept your word, and even to those who will doubt you” (3). I won’t go into too much detail here, but this idea that we must tell our stories – even when we face doubt – is compelling, as it brings into forefront the idea of how truthful we must be when we share our stories, how honourable, how detailed, and how who we are as a person plays into this. If we are a lying, conniving person with a reputation as such, who will believe us? If we live with good intentions and try our best to be straightforward and honest, who will believe us? The idea that doubt will always exist and we must simply still keep pushing against it, making our voice heard – compelling.

Another story I read was Grandfather Bear (11). There is a Bear present who is the Grandfather of the hunter within the story. Grandfather Bear helps bring the man and woman back to the main camp, and the boy speaks with him. I mention this story because of the human/animal relationship present. Often, animals in the more traditional stories carry the souls or spirits of past family members – we still see this is a lot of pop-culture – and the idea of either reincarnation or a re-claiming of soul, is shown. There are other factors about this story that made me take not e- the idea of roles of women, mourning, how a Chief is chosen – and I also think about how the idea of Chief’s are undertaken, as well as what we would call them in our own languages – but I wanted to examine human an animal relationships here.

Th last story I looked at was The Last Rain Dance (61) and this one touched on the time when the First Nations had been put on reserves, and they were still performing their spiritual ceremonies. The Elder performing the Rain Dance – specifically, the buffalo head pull where the skin is pierced and they dance through pain and ceremony for their families and ancestors – said not to perform that part, as government officials were planning on coming to the ceremony. One man did not heed the warning, and he danced but his skin tore, and he fell in front of the government officials who did not understand the ceremony, and hence, the ceremony was banned. He notes that because this ceremony was banned for many generations, that many of their people lost their language and the understanding of how life is valuable. This is important to note as the idea of lost language is prevalent throughout the book – the author states his intention to write these stories in the Saulteaux language – and we see how language is tied within culture. There is also present the huge cultural chasms between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, and the power dynamics present, unfair as they are. Who are these non-Indigenous people to tell Indigenous people where to live, how to pray, what to eat, and so on.

It’s quite appalling.

Even more so when you realize not much has changed.

Buy the book: Earth Elder Stories