In general, I thought this book to be akin in form to Highway’s The Truth About Stories – using plain english, oral traditions, and emphasizing the fact that these are her stories an her truths.

“Using prose and poetry, she confronts white colonial society with shocking and painful truths that make any person of consciousness re-evaluate their current thinking patterns. Her work is not light reading as issues of gender and race are not light subjects.” – source

I enjoyed that, although I was reminded multiple times that this was originally printed in 1988 and reprinted in 2003 – so the original tellings are already almost 3 decades old. I felt disconnected from her rants at points, and since this is her personal experiences told, it was easier to dismiss them as my own personal experiences woman have not been like this. That being said, who am I to say her points aren’t valid because I haven’t experienced them as an Indigenous woman, or don’t share her viewpoint?

In the preface, she admits that “my original intention was to empower Native women to take to heart their own personal struggle for Native feminist being” (vii) and that we have the responsibility to recreate our stories. She says, “We did not create this history, we had no say in any of these conditions into which we were born (nor did our ancestors), yet we are saddled with the responsibility for altering these conditions and re-building our nations” (x). It’s a powerful concept – that we must take responsibility if we are to fix our futures – but we can handle powerful.

She does address the fact that are her personal stories and experiences – “they are presented as I saw them… if I was not really there, it does not matter” (5). This allows her to be the main narrator and tell events and ideas from her perspective. She begins with how she was incredibly sick and was dying, from something no one was able to figure out, and she was sealed through love and faith and spirituality. She also speaks to the idea that women are more than mothers – a concept I hearty agree with – and that a woman must take time out to be with herself or her lover, to celebrate her being a woman.

In her initial chapters and throughout the book, she adds poetry and finished poems throughout, using lyrics to convey experiences and truths. She weaves her ideologies about parenting, sexuality and womanhood together, signifying that these roles often flow into one another but have separate meanings, especially the idea of sex and love, and how sex does not equate love, and how we should not teach our children that. Sex and sexuality – desirability – are a complicated thing within Indigenous identity, as we as Indigenous women are often seen as non-desirable even by our own men (and this is where she will lose me, as this experience does not reflect my own, but the idea that in main stream society that we hold certain stereotypes, yes, for sure) and we are seen as a place where the more ‘savage,’ if I may, desires could be slated.

She speaks of the idea of homosexuality in her Chapter “Isn’t Love A Given?” (20) but she states from the beginning that she is straight and cannot speak of what it is like to be a lesbian, but she can write about the homophobic behaviours she has witnessed. She speaks how women’s power is often ignored – in healing circles, at gatherings, at feasts where they do a majority of the work yet they are often overlooked – and that we cannot use the word traditional when speaking of how men used to treat women in our societies, as we are consenting to oppressive behaviours when we do that. Like the standing behind the men, etc. But when women love women, people object to the fact that these women are making a choice, and what right do people have to decide for someone else who they must love. All valid, but she loses me again when she says women choosing to love women are opposing rape, as sex and marriage between a man and woman equates to rape often – as women often feel they cannot say no in bed. This is a faulty argument as it’s under the idealism that are between women and women cannot happen, and the idea that marriage is allowable rape, both false presumptions.

She speaks of claiming her story for Indigenous women and people, that she is writing for her own peoples, as well that we have a terrible tendency to drag one another down. Lateral violence within our ranks is easy to see, hard to escape from, if we should even want to escape, as achieving success in a Candian society may not be something to be proud of if you’re an Indigenous person – because what have you given up to become successful?

She embraces the idea of Feminism and Indigenous Feminism – fighting for equality amongst men and women and Indigenous men and women is not a hard concept. It’s the concept of white feminism that she disregards – she refuses to take part at that table, where women will not acknowledge the intersectionality between culture and genders (15 onwards).

Note: While there is hella more stuff to deconstruct here, this book needs multiple read troughs. It’s powerful. I don’t always agree with it, obviously, but there are truth bombs dropped here and there that resonate with undeniable truths and are spelled out in a way that even the “everyone is equal and I don’t see colour” crowd can’t deny, which is good.

Quotables:

- “I learned the art of parenting is all about providing one’s children with the best possible condition in which they can grow” (9).

- “Though I hold no animosity toward the Europeans in this land, I do not intend to write for them” (10).

- “Each time I confronted white colonial society I had to convince them of my validity as a human being. It was the attempt to convince them that made me realize that I was still a slave” (14)

- “I want us to set the standard for judging our brilliance, our beauty and our passions” (17)

- “Tradition is useful only insofar as it allows us to continue to make use of our history” (89)

- “To ask our students to forget the past is to negate their present. The present they enjoy is not disconnected from their past” (91)

- “Decolonization with require the repatriation and the rematriation of that knowledge by Native people themselves” (92)

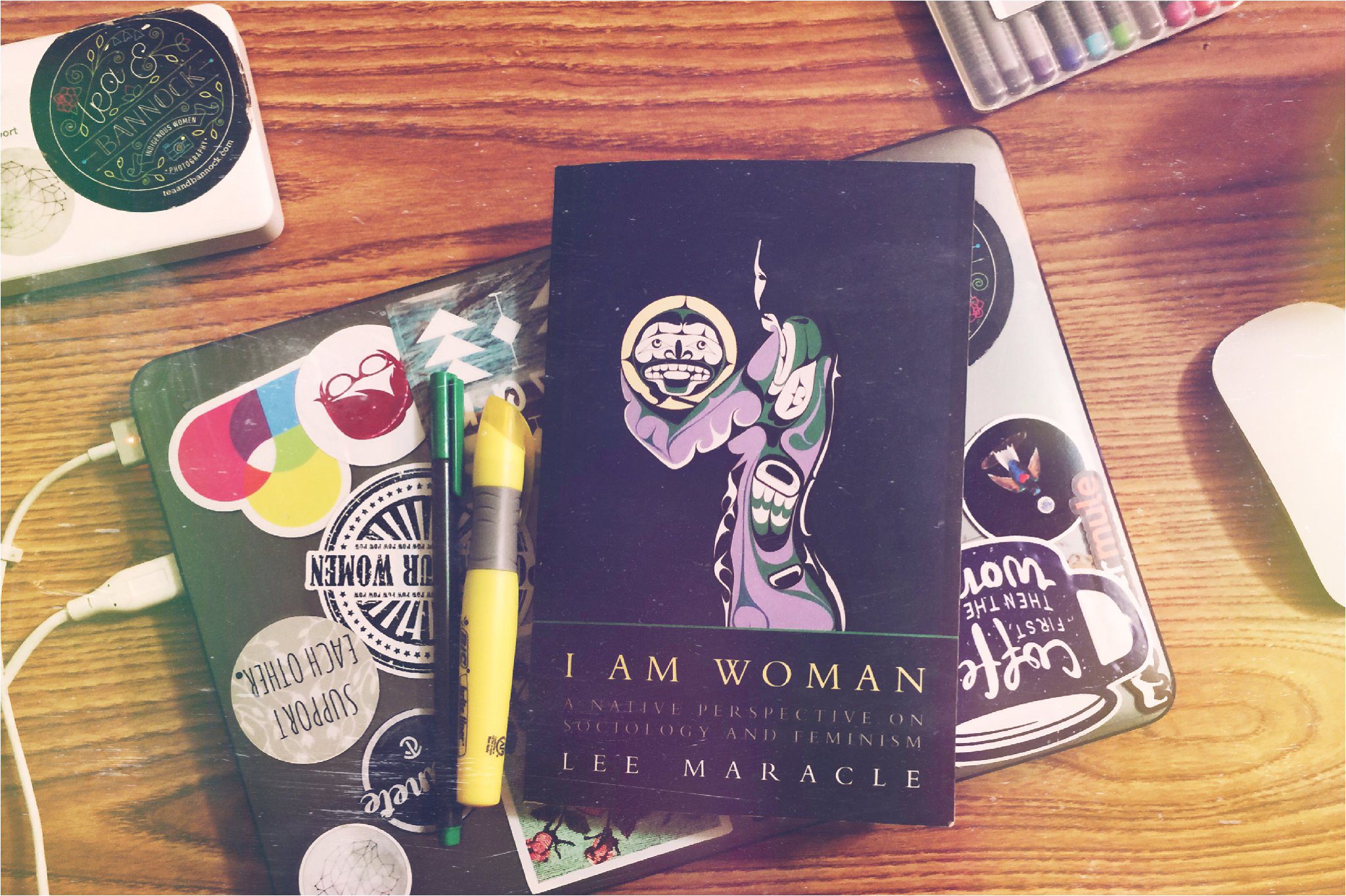

Buy the book: I Am Woman: Lee Maracle