This book is full of strong visuals and a sly sense of humour. The poetry reads from multiple perspectives, often employs a darker humour – survival humour? – but is comforting in how brash and head-on the reader is allowed to confront unsettling topics, such as spousal abuse and woman’s periods. It is divided into four sections, but it is in the afterward that Louise speaks directly to the process of discovering this book of poems, and I find it satisfying that it a life long adventure, a journey.

Loving Obscenities – p.31

The poem is told from the perspective of a young woman who is remembering her parents. The poem switches between descriptions of them, the basic elements of how she remembers them – at first common descriptors such as “Indian Affairs glasses” and how her dad “walked stooped.” She describes the smell of “whiskey breath with spearmint gum”, placing us within a memory and moment, then the small remarks about the abuse and jealousy that permeated their relationship start – “a black and blue shiner/ every Friday and Saturday night” from “his drama attacks.” That her father would examine and look for “suspected / visiting lovers.” Finally, when she placed them together in the poem, she notes how her mother walked a step behind her husband as he muttered “loving obscenities” and how she would see through him, wearing “cheap Indian Affair glasses.” In a few short lines, she places three people in a gut twisting situation and managed to reflect upon the everyday despair of this situation – there is nothing that she could do, so she chooses to diminish the actions of abuse by dismissing their behaviour and focusing on the small, superficial wrong things about them. The speaker comes off as a younger person, repeating and mocking the words she may have been told about the abuse. It’s a strong statement, to start and end with the glasses, perhaps a remark on both the indigenous aspect of her mother (her father’s culture was never mentioned), or a comment on how her mom’s view on her life was filtered through cheap and poorly made spectacles – there fore she didn’t see clearly.

First Moon – p. 46

A young woman’s first bleed, imagined in the traditional ways, of a lodge and wet moss. It is an exploration of a time that celebrated the strength of woman and blood, not shamed them. The writing shows us a woman squatting in the corner of a lodge, the smell of “sweet blood” in the air and how she feels between her legs and her fingers stick as “[m]oon rolled in my tongue, / around my fingers, and / in my bones.” She details, in blunt language, how we try to stop the flow of blood, even today with “I squeeze my legs, / tight. / I flow anyway, I flow. / I poke, I plug.” It’s a comforting and heavy poem, filled with the general confusion and happy daydreaming of first blood, of where the woman wonders if her baby will be a rabbit. The final image of wet moss between her legs as she sits in the lodge is a strong visual of remembering the traditions that came with first moon’s, once upon a time.

I’m So Sorry – p. 98

This is a push back or reflection about the apology the Catholic Church gave Indigenous People regarding Residential Schools. It starts out as an apology from the pope’s perspective, showing how he did not see how we used nature as offerings and blessings – that if he had known we had spirituality, he “wouldn’t have taken your babies / and fed them wafers and wine.” The second stanza is again, an apology/non-apology where he says he just wanted to borrow the land to build the proper kind of homes and places to worship and cattle farms, as “I really didn’t know how you survived / for centuries on buffalo and teepees, / praying in medicine wheel.” Th least stanza is a bit darker, with the pope apologizing for scalping – and the final section being still spoken in the pope’s voice as “Maybe I could build healing churches / chapels full of sweetgrass and drums / chase the spirits out and fill sweat lodges / full of armed angels.” I think this is a suggestion on how the pope could actually prove he is sorry – as it’s the actions that count, not the words. But the idea of armed angels in sweat lodges is a contradiction of spirituality from Indigenous and Non-Indigenous cultures, and “armed” refers to violence, so I’m actually to too sure where that went, but it’s always good to have questions, I think.

—

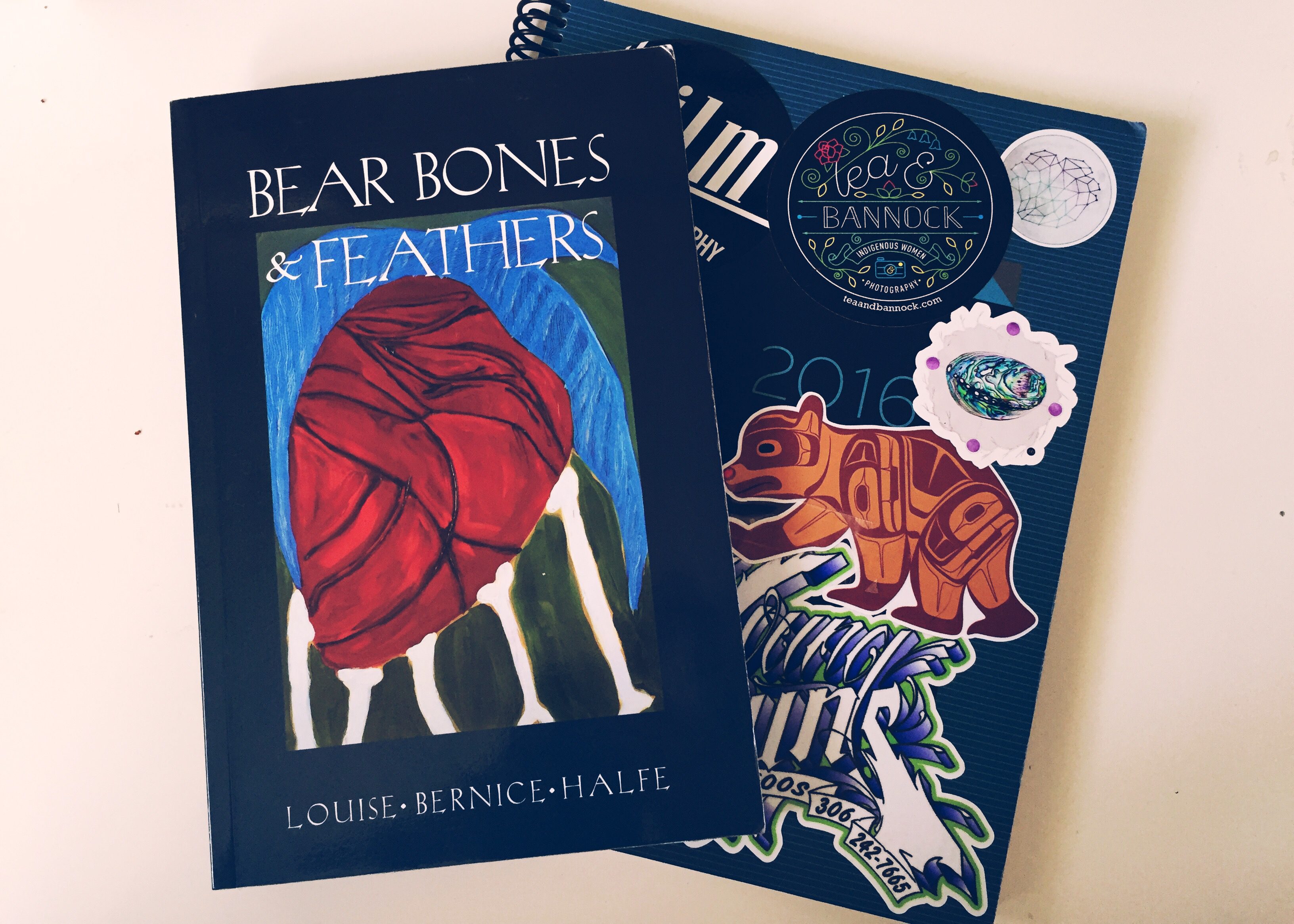

Buy the book: Bear Bones and Feathers, Louise Bernice Halfe